Congestion pricing and the way forward for NYC

Supporters of the plan are right to be mad at its suspension. But there are a lot of reforms the Big Apple can do independently that it has neglected. It should do them today.

Yesterday, New York Governor Kathy Hochul announced she was postponing the implementation of congestion pricing. Proponents of the plan are treating this as an existential threat, and they are putting on a show of force to persuade Hochul to reverse herself. And good for them. Congestion pricing is a sound policy. First proposed in NYC by Mayor Michael Bloomberg in 2007, it has been through the wringer even by local standards, including being killed and revived and 4,000-page environmental-impact-assessed and delayed and litigated over and over in the past 17 years, and now postponed indefinitely at the 11th hour. It was due to go into effect June 30 and instead it now appears a significant amount of federal grant funding and transit capital programming is in jeopardy.

It’s bad that it’s (probably1) being suspended and I sincerely hope Hochul reverses herself. However, what inspired me to write this post (and thus get off the fence and launch this occasional Substack) is not the sense of disappointment I share with other congestion pricers. Rather, I want to sound a hopeful, if critical, note about other options irrespective of events.

The uncomfortable reality is that NYC and the state Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA), which are the victims in this story, share a huge amount of responsibility for the pickle they now find themselves in. On the positive side, they have a huge amount of power to get themselves out—with or without congestion pricing.

The case of congestion pricing is a species of a larger problem: entrusting the city’s future to outsiders

The unfolding congestion pricing saga is not the first case of the city’s interests2 clashing with Albany—far from it. NYC Comptroller Brad Lander compared Hochul’s action to the state undermining NYC’s fiscal capacity 25 years ago by abolishing the commuter tax:

Unsurprisingly, that decision was also driven by electoral considerations.

I find it hard to get exercised about the political dimension of this dispute. Cities always have interests that are in tension with state and other local governments. In the case of NYC specifically, the relevant governments are too numerous to count and spread across three states. In our vetocracy, there will always be some powerful politician or agency with the juice and incentive to throw up a roadblock, whether it’s Andrew Cuomo, Chris Christie, Shelly Silver, Kathy Hochul, Donald Trump’s Federal Highway Administration, or Robert Moses’ various authorities. In 1999, suburbanites didn’t want to pay a commuter tax; today, they don’t want to pay a toll to drive into the city. Sometimes they also lose those battles of course. These conflicts are inherent in our system of government and there’s no wishing or legislating them away.

However, NYC is not some bit player in the 22+ million person New York-Newark, NY-NJ-CT-PA Combined Statistical Area. It is the principal city by population, jobs, income, wealth, elected representatives, and so forth. It is the global capital of finance, culture, and less important things. And it has quite a lot of legal authority as cities go relative to its state government. If power were a weapon of war, NYC would be the first nuclear-armed metropolis.

If power were a weapon of war, NYC would be the first nuclear-armed metropolis.

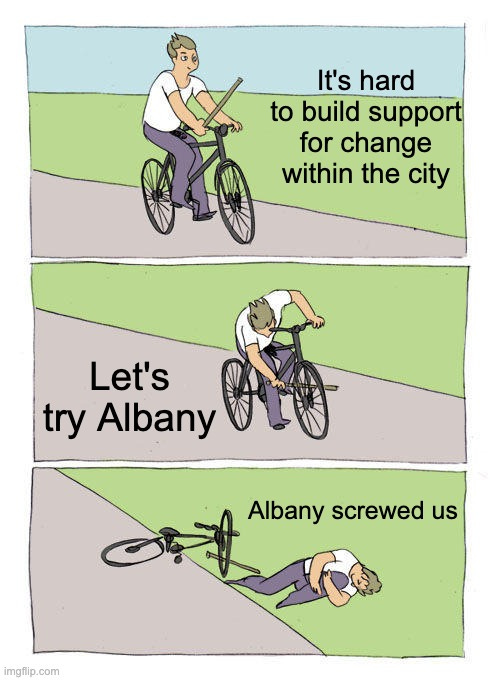

Stepping back, therefore, the general picture is not only one of failed cooperation across political boundaries; it’s also a question of why the city has failed, over and over, to seize the levers it already controls. (The same could be said of the MTA, a state agency, though this post focuses on the city.)

The TLDR answer is that it also turns out to be hard to piece together a winning coalition for change at the level of New York City government. But relying on air cover from Albany is not a risk-free alternative, as this episode illustrates.

The call to urbanize New York City must come most loudly from inside the house

Lander’s critique and similar “here we go again” handwringing by other advocates of congestion pricing isn’t wrong, but it proves too much. If the state has been obstructing the city on public transportation and other urbanist priorities for decades, why hasn’t the city adapted its own posture to account for that? It is not a passive actor in this story. It has agency.

Congestion pricing is a means to an end (ends, actually; more in a moment). Those ends can also be advanced by other policies. The city probably cannot do a comprehensive congestion pricing scheme on its own, legally speaking.3 The available substitutes are imperfect, but they would help. Even as it presses Albany for a reversal, this would be a good time for the city to draw up plans to abandon its pattern of learned helplessness.

The list of things NYC could do to substitute for congestion pricing is long, and I’ll discuss some ideas I view as especially promising in a moment. First, let’s talk about what congestion pricing was supposed to do.

Congestion pricing is not a skeleton key

The theory of congestion pricing is to use the price mechanism to redistribute demand for trips into the central business district away from private automobiles and periods of peak demand into transit and off-peak hours. Economists love this mechanism—want a way to allocate a finite resource like road capacity? Slap a price on it! Worried about regressive effects? Do some redistribution! The plan calls for this, and I generally embrace this theory.

However, pricing entry to peak areas at peak times is not the only tool available for encouraging such a shift. It is not even the only price tool. It is instead one among many—and one that, because it requires state and federal authorization and extensive regional cooperation, faces unique challenges in the actually existing system of government we have in the United States, which pits state governments and the national government against cities and does not have meaningful regional governments.

On its own, congestion pricing is not sufficient to achieve its goals and it’s probably not necessary either, though it may be hard to replace in the near term. The bottom line is that 1) it’s good but 2) there are a lot of other steps the city needs to take regardless of what happens.

Congestion pricing is hard

My hammer/nail bias is towards institutional challenges, and it’s my observation that economists often do not think enough about them. But my beloved fellow urbanists sometimes also seem to want to assume a can opener rather than asking why something that seems so elegant in theory is so hard in practice.

I enjoyed the quips that Chicago or Philadelphia or LA or Boston should show up NYC by being the first to adopt congestion pricing (seriously, go for it!). So, why have none of these pre-automobile metropolises, or indeed any American city or metro, done so since Singapore proved the concept in 1975? “Even the structures that govern urban America are car-obsessed,” okay, but if that’s the point of departure how do we get either congestion pricing or the benefits of it?

People don’t like to pay for things they are accustomed to receiving for free, such as the “right” to drive into Manhattan at rush hour. More specifically, and especially in a democratic system structured like ours, congestion pricing poses a classic concentrated costs, diffuse benefits problem. The Westchester resident bears a concrete, definite, and immediate cost and uncertain benefits. Meanwhile, the city resident who doesn’t have a car may not bear costs of congestion pricing, but the benefits of subway improvements slated to be completed in the 2030s, or even of reduced traffic, are uncertain. One could go deeper on the political analysis (suburbanites are credible swing voters and have outsize power, etc.) though I will leave that to others.

Not wanting to pay for things isn’t the result of some motordom conspiracy; it’s human nature and a storied American tradition.4 I have written about how lavish subsidies in US law and policy artificially lower the price of driving in general and driving recklessly in particular. But those subsidies are mostly unseen. There is some work documenting improved public perceptions of congestion pricing after its implementation, but to test if those studies are extendable to the US context you need leadership. The enthusiasm of scholars and advocates for this experiment has not been matched by politicos.

Those of us who care about cities, transportation, and growth should not simply give up on congestion pricing. Far from it. But neither should we resign ourselves to defeat if it gets mothballed.

The everything-bageling of congestion pricing

Though I traced the general theory of congestion pricing above, there is no definitive statement of the goals of congestion pricing. However, if you follow the issue (or for example take a spin through the MTA site dedicated to the topic), you’ll see the policy really has two classes of beneficiaries. It’s worth breaking these out distinctly.5

First, and most awkwardly, it benefits drivers themselves by increasing their travel efficiency. Traffic moves more freely after cities adopt a congestion charge, and suburbanites—who may have fewer good transit options than city-dwellers,6 and also have higher earnings on average—should have a higher willingness to pay for time savings. However, it is unclear whether drivers who would be hit by the charge give this much thought. We can debate the true intensity of opposition among suburban median voters, but at a minimum they are not exactly the ones clamoring for congestion pricing. Suburbanites as a group (or a powerful subset) either subjectively value the time savings less than the charge, don’t believe they’ll save much time at all, or on a more basic level just resent another “tax” on living in the tristate area. I would understand this as part of a more general cognitive aversion to price increases that prevents people from rationally weighing them against the benefits they bring. Perhaps for this reason, NYC’s congestion pricing plan was never primarily sold as a benefit to drivers or suburbanites.

Instead, the primary beneficiaries under the plan as marketed were more diffuse, but numerous and identifiable enough to have political clout. The main benefits are said to be:

Increased funding for transit ($15 billion for capital projects)7. In addition, if congestion pricing prompts more people to ride transit, that might boost revenue, which could in principle be used for operating costs.

Revenue is probably the most identifiable output of congestion pricing and the hardest to replace through direct appropriation, given the scale. Billions in federal matching dollars also hinge on this stream.

If you’re curious what the MTA can buy for $15 billion, the answer is “not much relative to its peers.” Its capital costs are the highest in the world, and far higher than in peer transit agencies in other countries, as the NYU Marron Institute Transit Costs project has documented.

For example, a proposal to extend the Second Avenue Subway by 1.5 miles is projected to cost $7.7 billion and won’t be finished until the 2030s. Most observers regard those estimates are optimistic.

Increased transit efficiency. Faster-moving traffic facilitates faster buses, which makes bus travel more desirable, creating a positive feedback loop of utility and ridership.

Environmental mitigation. This would operate both directly (by reducing traffic and emissions) and indirectly, through an accompanying fiscal commitment to mitigating the impact on areas already disproportionately harmed by emissions and that would face even more emissions under the plan.8

Improved road safety. Eliminating car trips or swapping them for transit use might translate into fewer crashes, injuries, and fatalities. It’s worth asking how sanguine we should be about this in the absence of complementary changes, including an enforcement push (probably not forthcoming), as less traffic would also mean higher speeds.

Congestion pricing in this form represents a significant expansion from the original concept (captured by the name) of trying to discourage traffic congestion. Now it serves several load-bearing functions fiscally and politically, making it an example of Ezra Klein’s famous everything bagel metaphor for why the US can’t build infrastructure (in brief, everything bagels are amazing but if infrastructure planning requires that every single topping be included, often the result is no bagel at all).

Though the revenue stream is hard to replace in the near term, the city has tools at its disposal to make progress on all four benefits without congestion pricing.

The people of NYC are the ones they’ve been waiting for

Suppose congestion pricing is canceled or mothballed. What can New York City do? A lot, it turns out.

Here are five ideas. A few have been done in some measure but could be massively scaled up. They are all complementary to one another and to congestion pricing, if it does happen. They aren’t easy but are worth the lift—and, crucially, their success or failure hinges on the city’s ability to get its act together internally, rather than to coordinate with forces beyond its control.

Increasing municipal revenue

NYC should turn on the population printer that is land use deregulation and decide it wants to be a larger, more prosperous, and more economically diversified city. Demand to live in NYC is off the charts (look at the prices per square foot); upzone and reap the benefits in population, wealth, and fiscal capacity for generations to come.

Many streets above 14th Street and in the outer boroughs are too wide. Instead or in addition to taking a lane for bikes or a sidewalk, take another lane in high-demand areas and auction off the land to property owners to add accessory commercial units on the ground floor. In pedestrian-swamped areas like some streets of the West Village, go full pedestrian and allow ACUs. Watch those sales tax (the city’s rate alone is 4.5%) and property tax receipts roll in.

The reason these land-use things are really transportation things is simple: in NYC, increasing density translates pretty mechanically into increased transit, walking, and biking access, which do all the positive feedback loop things.

The city should also do value capture, to recoup the costs of transit and street improvements by tweaking property taxes. Unless the city got really ambitious (e.g., started its own transit agency), this would likely need to be in cooperation with the MTA. Seems like the MTA now has an incentive to find a new funding stream.

Reducing transportation costs. In the medium term, shrinking the cost structure of all things NYC operations and capex through automation, standardization, consolidation, and pension reform is imperative. In the near term, I would probably try to figure out other ways to subsidize road services. For example, at least half of the NYC DOT budget is really about roads. See next item.

Transportation demand side. No one knows how many free parking spaces there are in NYC, which is how you know they’re not regarded as a scarce resource (even as every driver complains about inadequate parking). One estimate is 3 million free spots (!) for the 2.2 million cars registered in NYC and the many more owned by visitors and by residents committing insurance fraud.

On the margin, a residential permit system would curb demand (including from commuters), raise revenue, cut down on insurance and license plate fraud, and have other beneficial effects.

A permit charge of, say, $150 per year plus value capture (1.(d) above) might be enough on their own to replace lost congestion pricing revenue. The price of metered parking (as low as $1.50 an hour in some places—less than downtown Iowa City) and garage parking taxes can always be increased as well.

Transportation supply side. While the buses and trains are run by the MTA and other state agencies, and so their frequency cannot be increased directly by the city, streets are largely owned and operated by the city. Roll out bus lanes for every major route and actually enforce them, and not only with cameras on buses. (Oh, the NYPD doesn’t want to do the enforcement? Well, the suburbanites don’t want to do congestion pricing. Figure it out or give some responsibility to NYC DOT.) Remove parking to do this where necessary.

Safety and livability. Enforce speed limits. Bring back and strengthen the Dangerous Vehicle Abatement Program. Confiscate cars from reckless drivers. Can’t do that? Put one of those annoying orange stickers on the window like the sanitation department used to do. Further to item 1.(b) above, reallocate excess asphalt—a thing the city mostly controls!—and replace it with better uses, including some like streeteries that have nothing to do with transportation but are simply a repurposing of public space.

Finally, I would encourage advocates to take seriously the possibilities for filling the holes left by the possible failure of congestion pricing. For example, one aim was emissions mitigation. There are other ways to do this—including some, like electric vehicles, that don’t advance the traditional urbanist agenda of Amsterdam for all. But increasing the proportion of cars and trucks in NYC that are electric will improve air quality, with benefits for both health and livability. The city has the power to do things like expand EV charging, introduce preferential parking for EVs, and so forth. There’s a prior question here for advocates of whether maximalism or pragmatism delivers the goods. I count the current imbroglio as a point in favor of the latter.

Per reports, the Governor technically ordered the Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA), which is a public authority not under her direct control, to suspend the program. I haven’t dug into the scope of the Governor’s power to do so, either in general or under the terms of the congestion pricing program in particular, but that is a threshold legal question that I imagine we’ll hear more about soon.

I will use “the city” or “NYC” as a proxy for the city’s interests. Obviously where the balance of those interests lies is a contested subject, and neither the NYC government nor the various agencies that govern important services provided in city limits, like the MTA, are unitary.

If the city found some clever loophole, I expect multiple state entities would step in to stop it.

Example: it’s been years since you lost the ability to check a bag for free on any of the legacy carriers, but people (normies, not economists) still complain about the fee.

There’s a lot of academic work and policy briefs on congestion pricing, both in the US and abroad. Rather than conducting a lit review, my aim here is simply to note and organize some of the claimed benefits of the NYC congestion pricing scheme.

I’ve sacrificed nuance here in the interest of brevity. It would be more accurate to divide these groups not into a simple dichotomy of suburbanites and city-dwellers but rather suburbanites and people who live within NYC but far from transit on one hand and people who live close to transit, especially but not only within NYC, on the other hand. But that’s a long sentence.

Congestion pricing was estimated to generate $1 billion in revenue per year, and this future revenue was going to be pledged to secure a $15 billion bond for capital improvements to the transit system (not to defray operating costs). Structuring the funding stream this way allowed the MTA to bring forward the benefits of the policy by many years, in exchange for taking on more debt.

Excellent debut on this platform! This picks up a theme I've been writing about: that the urban malaise so many of our cities seem to be experiencing stems largely from failing to recognize that they have personal and civic agency. Looking forward to reading more!

What about a city dynamic street occupation fee? Lots of cameras snapping lots of license plate pictures and charging, say, $0.1 per snap. Adjust the price by time of day and place and you have a pretty good approximation of a congestion tax.