I've got a bridge to sell you

What do the most important US-Canada crossing, Brooklyn Bridge, and Golden Gate have in common? Deep involvement of the private sector—which might be useful for the next generation of infrastructure.

How many times have you heard someone say, “…and if you believe that, I’ve got a bridge to sell you”? The assumption behind the expression is that bridges are publicly owned, and so they cannot be sold.

This is not exactly accurate. The reason for the ambiguity is worth a look, if you’re interested in the practical and institutional mechanics of building big things.

The Ambassador Bridge

Today, the large majority of road bridges in the US are in fact public, i.e., owned by one government entity or another. But that’s not a law of nature. Historically, many bridges were privately owned. Its owners charged tolls (or collected responses to riddles, as the case may have been).

This is not just a historical curiosity.

The Ambassador Bridge linking Detroit to Windsor, Ontario is privately owned1 today despite its systemic importance to both economies (it carries a quarter of all US-Canada goods trade by value).

Some bridges mix public and private properties in a way that would make Schrodinger blush. A new bridge, the Gordie Howe International Bridge, is currently being built next to the Ambassador. Soon to be the longest cable-stayed bridge in North America, it is financed by governments on both sides of the border but built by private entities under a public-private partnership (P3) structure that calls for the companies to receive progress payments, a completion bonus, and 30 years of payments afterwards funded by tolls.

Why the complexity? It’s a complex job.

P3s are standard in much of the world, especially in places that lack strong legal institutions and deep capital markets. I haven’t studied this specific project, but my guess here is the reason is more functional. None of the relevant subnational authorities—Michigan, Detroit, Windsor, Ontario, etc.—build immense bridges often enough to develop the necessary expertise in design, construction, project management, environmental mitigation, international coordination, and so forth. Doing it as a P3 provides a vehicle to bring all the expertise under one roof (the consortium that won the bid included eight different companies). In addition, some of the political questions about relative ox-goring and costs over time tend to be muted when the players involved are private entities, even though there were many layers of public accountability in the planning stage. P3 contracts require handback of the asset in good condition when the contract is up.

Financing Other Giant Bridges

Because building big things is complicated, expensive, and unusual, it’s not as simple as getting the local Department of Public Works, which normally operates rather than builds things, to build it. There is a useful analogy here to corporate law. It is useful to have a legal vehicle to raise equity and debt, manage the workers, sue and be sued, and so forth. In the case of a bridge, this vehicle can be private, public, or a mix. Often, ultimate ownership—title—and foundational planning decisions are public but much the rest is meaningfully private.

In New York, the Brooklyn Bridge was built by the New York Bridge Company, incorporated by special legislation in 1867. That link goes to the act by which the legislature incorporated the company; it included a few interesting stipulations, such as:

§ 7: NYC2 can at any time acquire the bridge for the cost of construction plus one third, but with a big catch: “provided the said bridge be made free, to be passed by vehicles and travelers without tolls or other charges.” (More on this shortly.)

§ 8: anybody willfully damaging the bridge is liable to the corporation for three times the damage they caused

§ 11: this section grants the corporation eminent domain rights akin to those enjoyed by railroads

§ 12: authorizes NYC to issue bonds of 30+ year duration to buy stock in the corporation

Regarding the financing, Brooklyn apparently paid for two-thirds of the construction and its bonds were not paid off until 1956, some 73 years after the bridge opened.3 The bridge is owned by NYC today. I have not researched the fate of § 7 above or whether it would preclude the introduction of tolls (currently, there are no tolls).

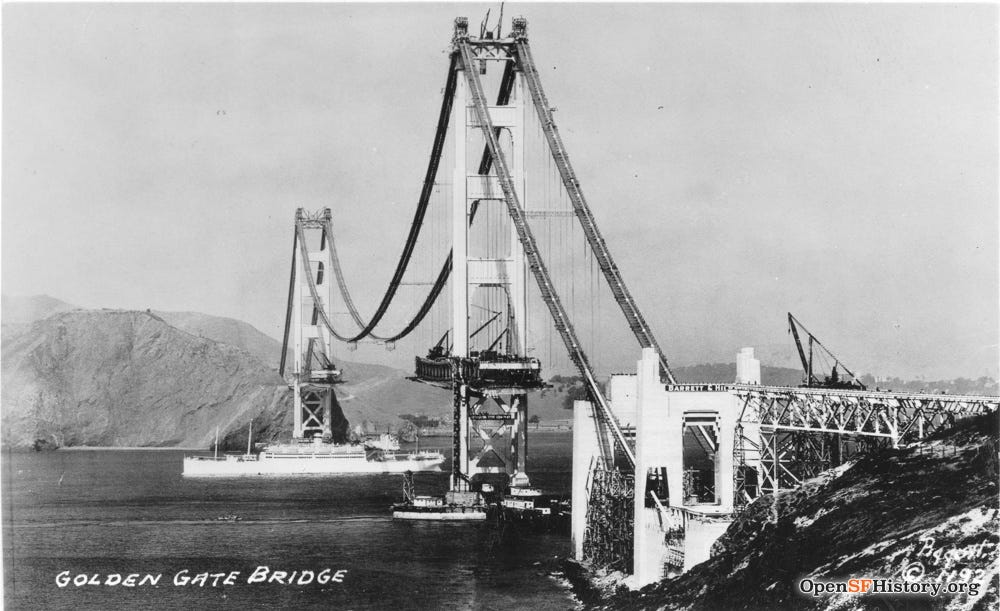

California took a formally different route to build the Golden Gate Bridge 60 years later: the special district, also known as a special-purpose government. How different this was in substance is a matter of perspective.

In a nutshell, the state legislature created a special little government for the purpose of building the bridge. That casual diminutive may be somewhat dismissive but it is also literal. A special district is not like a government; it is a government. These are very common; more than half the 90,000 governments in the US are special districts, including universities, water districts, parks, libraries, schools, fire, and police departments. The timing (1928) of the Golden Gate district was terrible in market terms and the district needed to then go get permission to sell bonds totaling half a billion in current dollars to get it done. No one bought the bonds, however (see market crash), but a local bank (Bank of America) played white knight. Today we have the bridge.

The bridge was built by private companies, but it was and is owned by the Golden Gate Bridge and Highway District. (The toll today is about ten bucks.)

What Do We Take From This?

Building big things is hard. The technical complexity, novelty, and uncertainty; various forms of financial risk (interest rate risk, inflation risk, revenue risk once it opens); and political and litigation risk4 all conspire to form a sustained headwind. In the best of circumstances, these ventures—bridges, subways, airports—take years to build,5 and any of the above can blow a project off course or kill it entirely.

This has been a major theme of the 15 years since the Great Recession,6 and the enactment of multiple laws under Biden providing historic funding to infrastructure has confirmed that money is necessary but not sufficient. The institutional stuff is a problem, and it is hard. With a new administration in Washington that’s unlikely to favor big public projects, blue states showing no interest in (and sometimes active hostility to) fixing the process by which they are approved and managed, and interest rates remaining stubbornly elevated, I don’t have much confidence in this improving anytime soon.

Especially now, I think it’s important to take an ecumenical approach to project structure—one that is used in many places around the world—rather than letting provincial and simplistic late 20th century US political debates about the merits of privatization dictate what we do.

Project Finance in the Late 2020s and Beyond

One lesson in doing big projects is that it’s helpful to have one entity of some kind that “owns” the mission. This creates not just the risk of public embarrassment but actual legal and economic exposure. That entity can be a corporation. It can be a special district.7 A P3 could also be described this way.

Big projects are like firms all unto themselves. It’s true of building them. It can also be true of operating them.

You could imagine a conventional corporation building and/or operating infrastructure. Examples abound. Tokyo Metro, already a private company, offered shares to the public in October 2024. It was Japan’s biggest IPO in six years. In the US, Brightline, a private company, owns and operates a small but growing intercity rail network that’s highly regarded.8 Then there are one-offs like the Ambassador Bridge and P3s, like Maryland’s Purple Line. There’s a pretty rich set of privately owned transit models, current and historical alike, and they usually have more flexibility to bundle transportation with land use investments. As a utility, like sewers or electricity, transportation infrastructure unlocks land value—which public entities are often not well positioned to capture and in some cases are legally prohibited from capturing. In some cases, private builders of transportation networks in the US and UK have also been barred from developing adjacent land, but the risks that attend such combinations can be addressed more thoughtfully.

All of which is to say that while there is a natural logic to international crossings and other major infrastructure being “owned” by the public, not all of them are—and even those that are, were often built, managed, or owned by private parties for a while. Some still are. Private capital, designers, builders, and operators have always been essential, even as there are large public programs today like TIFIA that provide low-cost credit. While P3s don’t have a positive reputation in some quarters (the Purple Line project has attracted a lot of criticism, for example), for a variety of reasons I suspect we’ll be talking a lot more about them and other private models in the next 15 years than we have in the past 15. The next time someone offers you the chance to buy (stock in) a bridge, don’t just chuckle; ask for the prospectus.

It was owned by an eccentric billionaire until his death in 2020. He acquired it when it was a publicly-traded (i.e., large private) corporation in the 1970s.

At the time, New York (Manhattan) and Brooklyn were separate cities. Each city was granted this right.

In a world where the bridge was publicly financed, it makes sense that Brooklyn would pay for most of it. Who needed it more, Brooklyn or Manhattan?

Even just within the category of litigation risk there are many subcategories: environmental, administrative, property rights, civil rights, procurement, etc.

There is scarcely a clearer example than the Second Avenue Subway in New York City. First approved in 1929, the first leg opened in 2017.

Market dynamics—a construction labor force thinned out by boom-bust dynamics, on top of unpredictable prices and timing for materials, etc.—exacerbate the institutional problems.

Today, corporations are overwhelmingly general rather than specific—they can be formed for any lawful purpose, not just to farm ice or build iPhones—and so to that extent the special district, not what we think of today as the corporation, is the successor to the special corporation.

Though weirdly deadly. In this case, I think those two are probably related; it is hard to imagine Amtrak killing as many motorists and pedestrians, for example.

"The bridge is owned by NYC today. I have not researched the fate of §7 above or whether it would preclude the introduction of tolls (currently, there are no tolls)."

Not sure if you meant "how the bridge passed into public ownership," but if you did, I like "The New York and Brooklyn Bridge" from 1883, by Alfred Barnes. It's a short retrospective on the bridge written right as it was completed.

"It was not until 1875 that Mr. Kingsley, on behalf of Brooklyn, and Mr. John Kelly, on behalf of New York, went to Albany as commissioners to solicit legislation granting an additional eight millions. By this time every one realized that a work so important and promising must not be allowed to lag for want of funds. The law was readily passed, and the cities voted the money in the same proportion as before—two-thirds of the amount from Brooklyn, and one-third from New York. At the same time, and in the same manner, the cities assumed the stock of the private stockholders ($500,000), that the bridge might remain an absolutely public work forever." (link to this excerpt: https://www.google.com/books/edition/The_New_York_and_Brooklyn_Bridge/EpsOAAAAYAAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&printsec=frontcover&bsq=It%20was%20not%20until%201875)

Thanks! Still curious about section 7. I have another book about the bridge sitting in my office, will look at it after the break.