Missing the Mark? An Exploration of Target-Date Funds

83% of Vanguard savers use target-date funds for retirement. These funds offer advantages—especially simplicity. What's in them?

If Vanguard funds are representative,1 most American retirement dollars are now going to target-date funds. This is often a product financial advisers recommend. How do these funds work, and what assets do they hold? I was curious about some of the particulars, so I took a look under the hood and wrote it up (along with some background).

Nudging into target-date

Whether you know it or not, if you have a retirement account there is a good chance that you invest in a lifecycle fund, also known as a target-date fund because it targets a retirement date (say, 2050). These funds have been celebrated as a premier example of successful “nudging.” Nudges involve changing a default setting of inaction (like failing to select any retirement plan at all) to a default action (like automatically earmarking 3% of your pretax earnings for a fund targeting retirement at age 65 unless you opt out of it).

As a policy, most would agree that the latter is better than the former. And to an employer that wishes to default employees to some investment, the choice of target-date seems defensible.

I’m interested in a different question. How should individuals making affirmative choices be thinking about the target-date option?

I’m not here to give investment advice, and this isn’t such advice. Everyone’s situation is different, and I’m not licensed or trained for that. Moreover, I’m writing in the shadow of deep literatures on finance and individual investing here that I will only touch the surface of. So, don’t rely on this to make any investment decisions. Rather than provide advice, what I will do is break down a few interesting attributes of the target-date fund and share some things I learned in exploring them.

How target-date funds fit into conventional investment advice (very briefly)

Standard investment advice recommends, in part, to hold a portfolio that is diversified along key dimensions and that corresponds to one’s risk tolerance. This advice normally counsels allocation across asset classes (e.g., buy both a stock fund and a bond fund rather than just one or the other) and diversification within asset classes (e.g., buy an S&P 500 fund, which contains Apple stock as well as that of about 500 other companies, rather than just Apple stock).

Given the widespread availability of index funds and ETFs (for bonds as well as stocks), allocation and diversification are trivial to achieve with or without a target-date fund. The innovation of a target-date fund is to rebalance the basket toward bonds automatically over time on a predetermined schedule.

The CW is to weight your portfolio toward stocks (riskier) when you are young and de-risk by gradually rebalancing into a higher proportion of bonds (less risky) as you approach retirement. The theory here is that stocks return more than bonds over time on average but with higher volatility, and so with a longer time horizon you want more in stocks, but with a shorter one—for example, as you near retirement—you accept the lower expected returns of bonds in exchange for their lower expected risk. Target-date funds generally do this for you.

If your employer sponsors a defined-contribution retirement plan like a 401(k) or 403(b), on your first day you were probably presented with a menu of investment elections. As a corporate law professor, I enjoyed researching my options, but I recognize that is unusual. The target-date product responds to the reality that many people don’t want to think about how to allocate or diversify, much less how they should rebalance over time.2

Hence the popularity of the target-date “nudge” out of paradox of choice paralysis. But it may be worth looking at what you’re being nudged into.

This, in turn, requires looking at the target-date portfolio through two lenses: allocation across asset classes and diversification within them. The second is more interesting, in my view. We will use Vanguard as an example, though at the end I look at two other leading fund providers (Fidelity and BlackRock).

What is in a target-date portfolio?

There is reason to believe a large proportion, perhaps a majority, of US retirement dollars are now going into target-date funds.3 What do those funds look like?

Especially since target-date funds are pitched to investors as set-it-and-forget-it products, it’s important to understand what’s in them.

1. Target-date fund allocation across asset classes

A glance at two Vanguard lifecycle funds with different target dates illustrates how they change asset allocation over time to become more conservative. The first image depicts the Vanguard 2050 portfolio allocation of ~90% stocks, ~10% bonds.

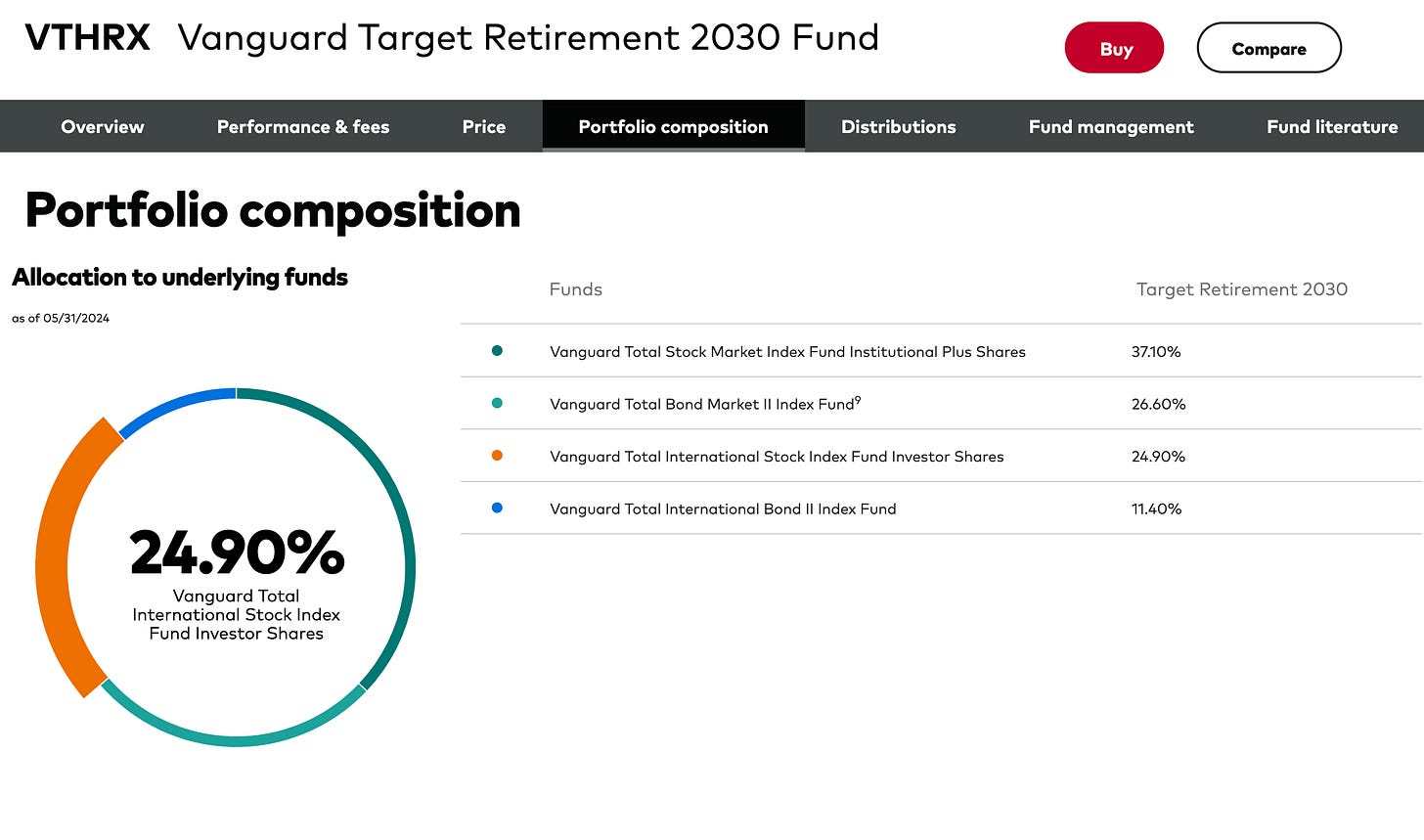

For someone planning to retire at the end of this decade, on the other hand, Vanguard’s 2030 portfolio allocation, which is ~61% stocks, ~38% bonds, might be more reflective of typical advice:

This makes intuitive sense and, I suspect, is broadly understood (if not in all its particulars).

2. Target-date fund allocation within equities

Now let’s have a look at how Vanguard allocates within asset classes—specifically, equities (stocks), where most of the returns are expected to come from.

As noted above, the stocks/bonds split in the 2050 fund is about 90/10 and in the 2030 fund it’s about 61/38. So, while the 2030 portfolio is more conservative, both consist mostly of stocks. What’s in their stock allocation?

Within equities, both portfolios maintain a rough 60/40 split between domestic and international. This is not totally clear from the pie charts in the images below, but you can get there with some basic arithmetic.4

Standard investment advice often recommends diversifying not only within US stocks but internationally. There’s a lot of research on this, but one reason is so that the investor’s position roughly replicates the geographic makeup of global equity markets. And, in fact, a 60% US weight corresponds roughly to the US share of global equity markets.5 So, on its own, the percentage allocation to international stocks is not notable.

3. What does “international stocks” mean?

Next step: what does “international” mean in the context of equities?

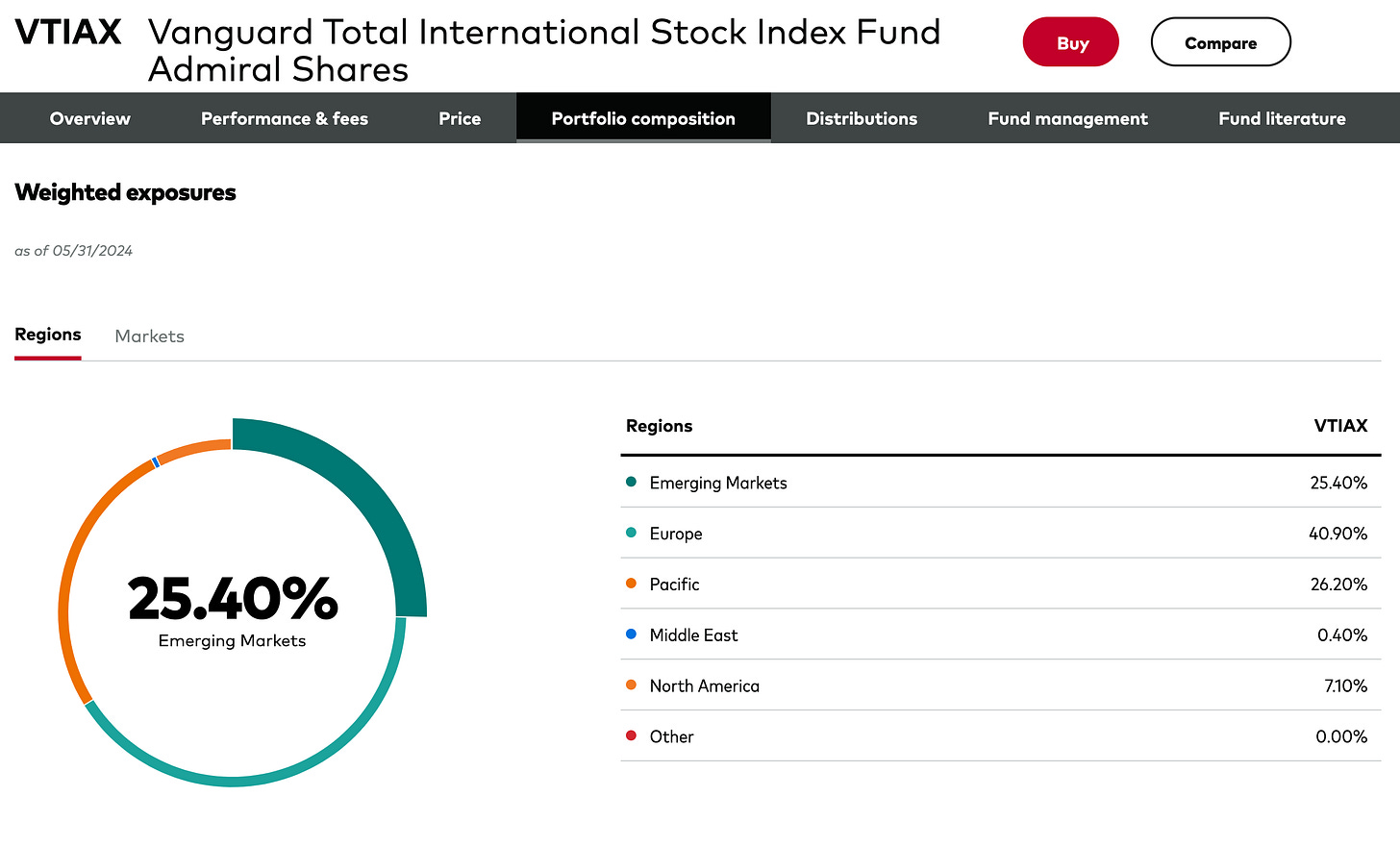

Both funds allocate to the same Vanguard total international stock index fund. That fund excludes the US6 and is weighted about 25% to emerging markets (see below).

This means:

For every $100 invested in the 2050 fund, roughly $9 is in emerging market stocks (25% in emerging markets stocks x 36% in international stocks x $100).

For every $100 in the 2030 fund, roughly $6.25 is in EM stocks (25% in EM stocks x 25% in international stocks x $100).

Is that good or bad? This post does not take a view. But I suspect most people would not guess that something like 5-10% of their retirement is in emerging market stocks.

What’s the deal with emerging markets stock?

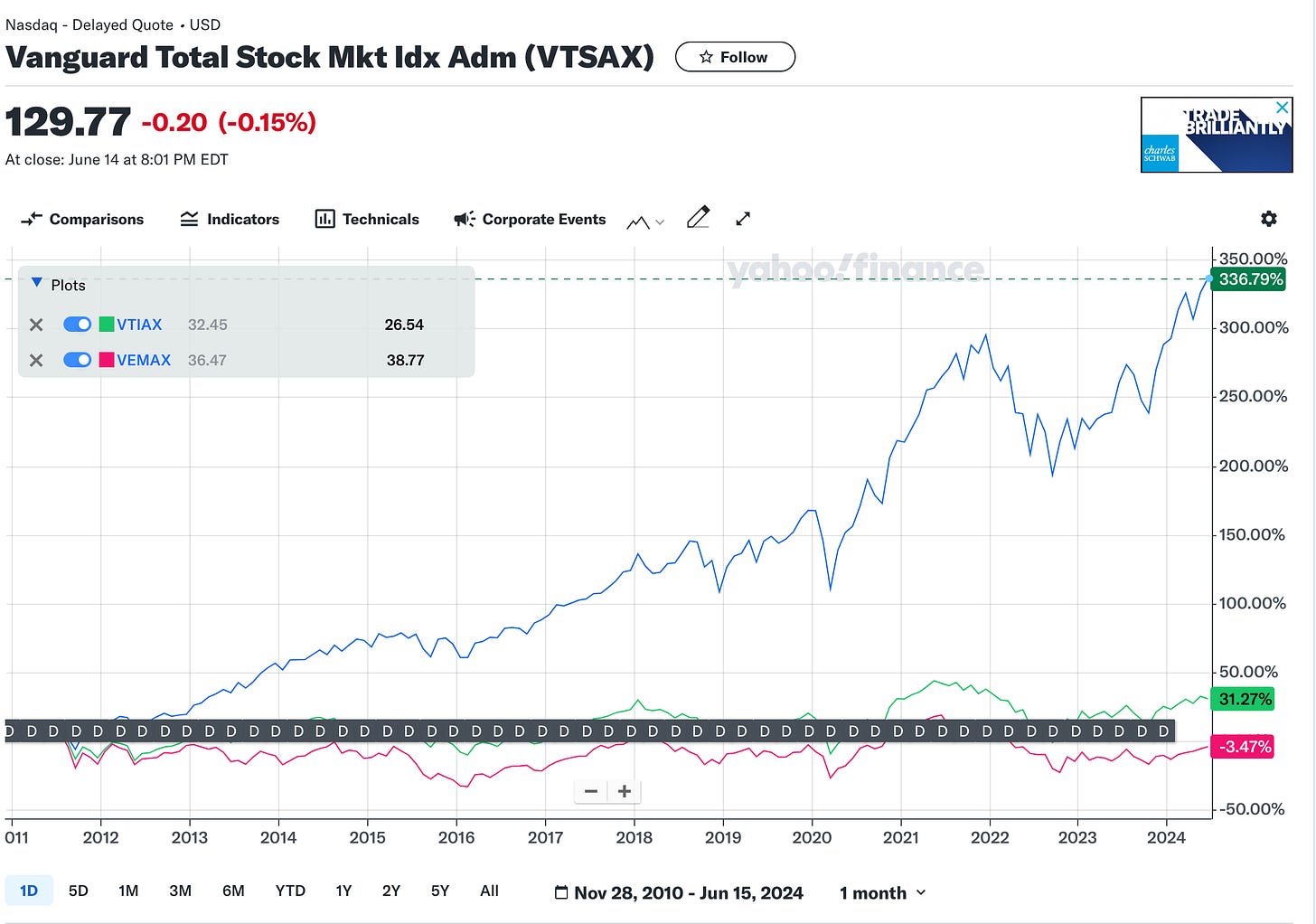

The increase in cross-border capital flows in the latter part of the 20th and early 21st century could be the subject of its own post—as could the history of emerging market stocks (and the marketing to Western investors thereof), which of course was part of that same story. There have been periods, e.g., in the 2000s, when EM stocks have outperformed their US counterparts, and they have a history of less-correlated returns with US stocks (generally something that’s recommended for diversification). The period since 2009, however, has been one of catastrophic underperformance relative to the US (and even vs. the rest of the world, which has also underperformed the US).

The following chart compares the performance of: (1) the US stock fund (VTSAX) housed in the target date product, (2) the international stock fund (VTIAX) housed in that same product, and (3) VEMAX (the Vanguard EM index fund), since late 2010 (date chosen because that’s when VTIAX was launched). In this period, the US fund returned ~11 times the international fund. Recall that this international fund is currently only 25% emerging markets—but the EM component got crushed. The EM-only fund (VEMAX) is down 3.47% since 2010, compared to the US-only fund’s cumulative 336% gain in that period. (The EM fund is a decent proxy for the EM component of the international fund.)

Is allocating 6-9% of your retirement to emerging markets stock a lot?

As noted, the 2050 Vanguard fund puts about 9% of your retirement in EM stock while the 2030 variant invests about 6.25% there. Is that a lot in comparative terms?

In a word, no.

Fidelity’s 2050 fund allocates 13% of to emerging markets equities; for the 2030 fund, it’s about 10%. For BlackRock’s 2050 product, it’s in the neighborhood of 9.5%7; for its 2030 product, it’s around 5.75%.8

In 2014, Morningstar issued a report on EM allocation that addressed specifically the question how much target-date funds allocate to EM stocks, finding the median weightings to be 4-6% of the equity allocation, which should be a bit less than that for the total portfolio—in other words, less than but within a few percentage points of where Vanguard, Fidelity, and BlackRock are today. One can find a lot of investment advice encouraging heavier EM allocations.

What to make of this?

This exercise taught me that, somewhat to my surprise, current leading target-date EM equity allocations are not far off from where they were a decade ago and the Vanguard allocation is not notably different from its peers. Emerging markets constitute something like 27% to 30% of global equity markets,9 so a target-date fund investor looking to gain global equity exposure proportional to global market cap might, if anything, be underallocating to EM relative to that goal.

These are questions I’m personally contemplating (it is not investment advice!) as an American investor whose income, assets, liabilities, and taxes are all in US dollars and mediated by the US political regime, and who lives in the US:

Do I want to diversify into foreign currencies, rate risks, and political risks at all?

These are questions investors in most of the world normally answer in the affirmative, even in, e.g.,, the UK. But the US capital markets are different (for example, we have individual companies, like Nvidia and Microsoft, that are worth as much as the entire UK stock market).

Would such diversification be an effort to increase average returns or mitigate tail risks? (two different things)

Within international stocks, do I want ~10% of my retirement invested in a highly volatile submarket that has lost money for 15 years while the domestic market has boomed?

With bonds, you trade lower performance for lower volatility; this isn’t the bargain with EM.

The counterargument, of course, is mean reversion. Viewed in this light, a 15-year period of underperformance is an incredible buying opportunity.

More provocatively, asset classes are an investment industry product. EM became trendy in the late 20th century, when it outperformed. Is it the right product, especially for Americans who have good reasons for home bias?

What’s the right proportion to allocate to EM? Beyond public equities and bonds, real estate, commodities, and classes that didn’t exist when EM was born (e.g., crypto) are widely available to retail investors.

I welcome any additional questions and thoughts.

A 2023 study by Vanguard, one of the largest asset managers, reported that the share of Vanguard plan investors who choose a lifecycle plan increased over 50% between 2013 and 2022, from just over half to 83%. See fig. 79. These savers have a choice about how much to allocate to different options, and they are directing most of their contributions to these funds (63% in 2022). I suspect the figures at the other top asset managers are only slightly lower, and that the trend has continued upward since 2022.

The target-date fund also provides diversification by being a multi-class investment, holding both stock and bond funds, but again this can be achieved simply buying stock and bond funds separately.

See fig. 79 of this Vanguard study.

Recall that the 2050 fund overall has a larger stock allocation. Stocks account for about 90% of 2050 fund assets and the international stocks component is 36% of the total portfolio, meaning that about 40% of the stock component of the portfolio is international (36/90 = .4). In the 2030 fund, stocks account for ~61% of fund assets and the international stocks component is ~25% of the total portfolio, meaning that ~40% of the stock component of the portfolio is international (25/61 = .41).

This share is believed to have risen sharply this year. The funds may rebalance at some point to reflect this.

US public companies generate a large share of their revenue overseas (for the S&P 500 the figure is about 40%), so even by investing wholly in US companies one gains exposure to foreign markets.

BlackRock’s geographic breakdown doesn’t distinguish between equity vs. bond exposure, so this figure is likely imprecise. You should be able to pin it down by poring through the fund documents.

Same caveat.

A lot hinges on which markets one designates EM and when the snapshot is taken. For example, Russia is now ~uninvestable to Americans. Regardless, the increasing outperformance of the US in the past few years likely tips the EM percentage of total global market cap a bit lower.

The term emerging market has a nice feel to it. You think you're capturing the "rest of the world", which is (1) supposed to grow fast as it converges to the productivity frontier and (2) be good for diversification since there are so many emerging markets out there. In reality, 70-75% of the holdings (e.g. Vanguard's VWO or BlackRock's EEM) come down to just 3-4 countries: China, India, Taiwan, and (sometimes) Korea.

Korea and Taiwan are basically developed countries and would be removed from the category if not for inertia (Vanguard already excludes Korea, while MSCI/BlackRock do not). China is weird; the economy grows, but the stock market is astonishingly stagnant. Some set of domestic idiosyncrasies or Party shenanigans seem to prevent rising valuations. The other 25-30% mostly lack diversified economies and swing with whatever commodities they specialize in.

That leaves India and a few small constituents like Mexico and Malaysia as representing emerging markets the way we abstractly think about them. You can either buy into financial theory (APT and cousins) and simply hold the total world market in proportion to market caps (presumably we'll start being rewarded for holding emerging market risks any day now). Or one can take views and specifically hold ETFs for India, Mexico, etc.

What wouldn't make sense is having some non-market cap weight to "emerging markets". The category is too heterogenous to be meaningful. Vanguard seems to be faithful to market cap weights, so their position is defensible even if it has underperformed for many years now.