Houses and cars can be albatrosses. What does this mean for policy?

Home and car ownership are unaffordable to many—and that's inherent in their cost structure. Would it be better for policy to accept this and build around it rather than merely trying to change it?

Houses and cars are the most expensive things Americans typically buy. They are, obviously, assets. But they are also liabilities. If not in the accounting sense,1 then in a very real sense: to continue to use them, you need to keep current on a variety of fixed and variable expenses. These costs are not always predictable and can be substantial. They can be albatrosses for poor families.

This makes home and car ownership, however desirable as consumer preference, a little awkward as universal policy goals. At any given time, a large segment of the population cannot afford to own one or either. Policy can try to make both more affordable (and it does try, especially for homeownership, with extremely mixed results). But it can’t fundamentally change this dynamic, because it flows from intrinsic attributes of these products—namely, their high operating costs. They aren’t software or t-shirts. They are physical things that cost a lot of money to begin with, then degrade with use and cost a lot of money to keep using.

This post describes the ownership burden of houses and cars. Their high operating costs, which include lumpy variable costs, makes them difficult for many people to afford, even with subsidies. The post then briefly examines some implications of this fact for policy. TLDR, we need to be improving conditions for everyone rather than expecting the house-and-car ownership model to deliver the good life.

The cost structure of the home

Right now, about 65% of Americans own their own homes, consistent with the rate over the past 60 years and only slightly below the OECD average. One could give many examples of the high-level priority assigned to policy promoting home ownership. Bill Clinton touted it in 1995 (in turn reaching back to FDR’s creation of the Federal Housing Administration in 1934), and here’s GWB’s self-described record of accomplishment on the issue (please just don’t mention the post-2008 period).

The potential benefits of owning a home—psychic and, if you’re fortunate,2 financial—are fairly straightforward. The costs, if not equally obvious, are at least more widely discussed than ever, for example implicitly by rent vs. buy calculators and explicitly by some personal finance gurus. (Any new homeowner will also be happy to tell you about all the stuff they have to pay for now that they didn’t as a renter.) These costs include but are not limited to:

principal and interest payments each month (with mortgage rates stuck near 7%, the latter is the large majority of the monthly payment);

property taxes;

insurance (currently skyrocketing);

utilities and upkeep (e.g., pest control) you wouldn’t be responsible for in a rental;

maintenance, repairs, and renovation (some discretionary, some essential);

extra furniture (same);

transaction costs (broker’s fees, inspections, title insurance, transfer taxes, etc.);

HOA fees in many cases;

the opportunity cost of the down payment and all the rest of the above (the CAGR of the S&P 500 over the last full 10 calendar years was 9%, after adjusting for inflation); and

diminution in economic mobility (and thus implied diminution in wages; a large share of raises come from job-switching, which may require changing locations).

The US median household wage in 2022 was about $75,000. However, as this chart illustrates, nearly a quarter of households earn under $35,000.

Can we expect a typical household earning, say, $35,000 a year to bear even most of the above burdens reliably and without stress or trading off other expenses, such as medications or food?

As a general rule, I think the answer is no. Some in this income group of course do own for various reasons. This post does not evaluate individual choices but rather policy assumptions. Tilting the scales in a way that puts more people in the sub-$35k income category into an asset like a house does not seem like a wise thing for policy to do.

Notably, even for the fraction of low-income households who own their home free of a mortgage, insurance, property taxes, and essential upkeep can be very costly—and the latter is unavoidably lumpy. An HVAC system replacement, for example, can cost $5,000-$12,000 but deferring the expense may not be feasible and financing may not be available or advisable at prevailing rates on this income. How about a new roof? A plumbing emergency? It’s hard to save for these things even at a higher level of income. Then you have tail risks like natural disasters not covered by insurance, which are essentially impossible to plan for.

Ownership is costly in precisely the kind of unpredictable way that is difficult to smooth for most people. Lending standards, down payment requirements, insurance requirements, and other hurdles are all reflections of the underlying volatility in people’s ability to shoulder these rolling expenses. At low incomes, the risk is very high. Raising real incomes via transfers would help on the margin, but the problem is inherent in the thing.

In brief, houses come dressed as assets, but they generate major liabilities. There’s no realistic path to universal ownership affordability, which is probably why even at the height of the 2000s bubble homeownership rates topped out at 69.2%,3 a peak followed by disaster (including about 3.8 million foreclosures between 2007 and 2010, representing over 1% of US population).

Car ownership can also be albatross-y

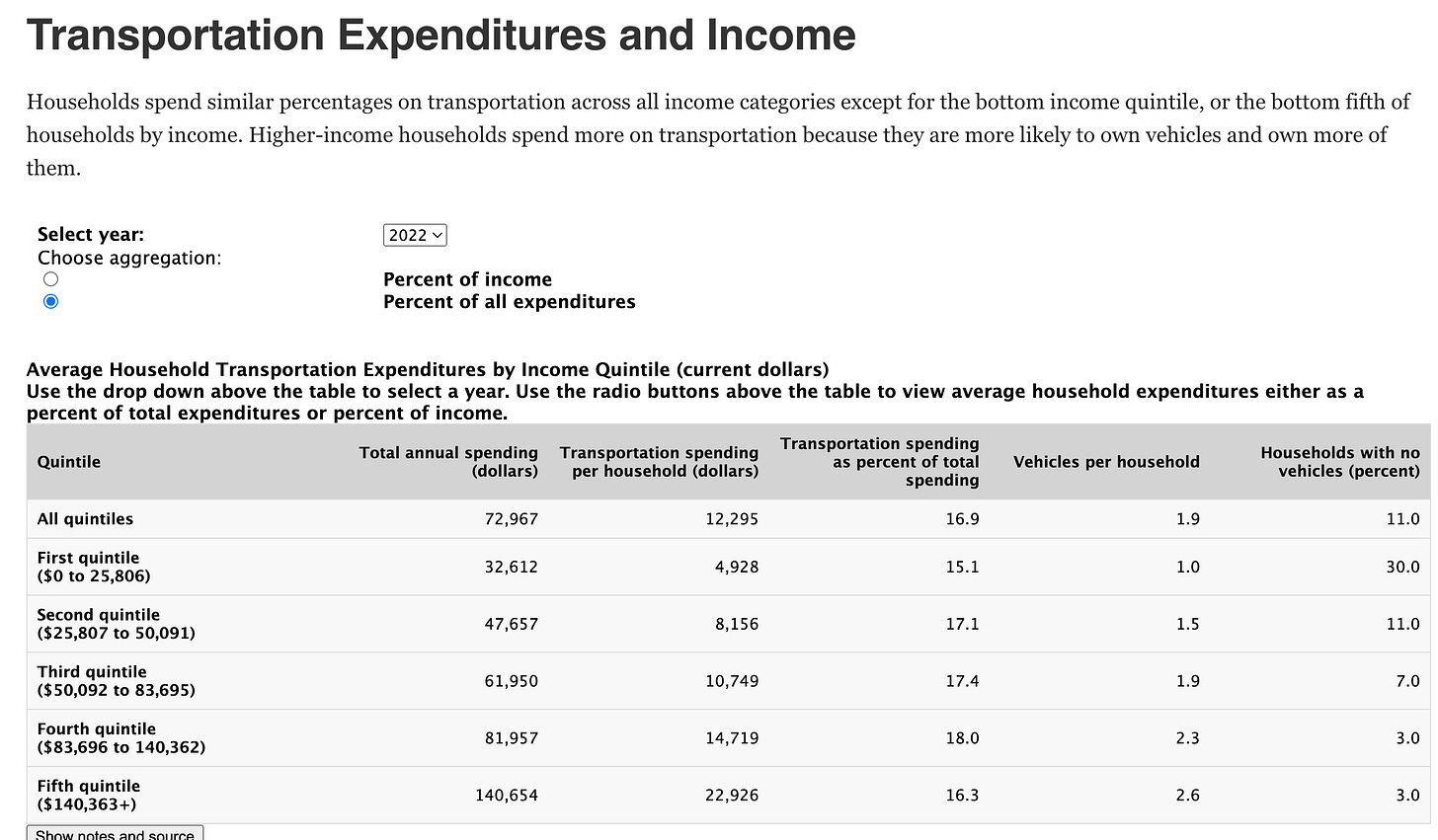

Per the Bureau of Transportation Statistics, the average household spent about $12,300 on transportation (overwhelmingly, personal vehicle transportation) in 2022, accounting for about 17% of total household spending across income quintiles, after only housing. The costs of operating a car include many of the same types of costs that apply for houses.

That’s a lot of money, but it’s also highly variable at the household level year to year. There’s insurance, maintenance, and repairs. Tires (easily $1,000), registration, batteries, oil changes, brakes—that stuff is table stakes, though in some years you’ll just need oil changes. Then parking, gas or electric, and of course crashes. Over 10 million (and possibly more than double that number) of cars are involved in crashes each year, with an increasing share being declared a total loss because the cost of repair and value of spare parts have both increased. Some of these costs are fixed or at least predictable, but many are lumpy.

As with houses, it is hard to efficiently smooth the expenses, especially at the lower end of the income distribution. To afford the operating costs, you need to either have a certain amount of money in the bank, access to credit at reasonable rates, or both. Some kind of subsidy that gives every driver $1,000 a year might help with tires one year but isn’t going to substitute for gap coverage the next when the car they still owe $30,000 on is declared a total loss worth $23,000, and they have to make up the difference and finance a new or used car at double-digit interest rates.

In sum, cars are expensive to operate. Yet as with houses, we assume everyone can own one.4 That’s unwise and inaccurate. Even in the Motor City, for example, 21% of households do not have a car. The high operating costs of cars and the inability of government to achieve cost savings via economies of scale (in contrast to, say, transit) make car ownership an unattractive candidate for direct fiscal subsidies in my view, even though such subsidies would have some employment benefits.

What would policy that is agnostic as to home and car ownership look like?

About one third of US households are renters and roughly one third of the US population lacks a driver’s license.5 As noted, while the response of existing policy to these percentages is to try to shrink them, it’s worth asking what else we can do. Because while home and car ownership confer many benefits, they can also be an albatross in financial terms.

Broadly, there are two ways to look at this state of affairs. One is to try to generate self-identification among this group of people who can’t expect to own a home or a car and build a distributional politics around them. I’m not a political scientist, but I am skeptical about this whatever one’s view of the merits. Many people are not permanently in this group, and some who are, aspire not to be. Also, relatively high home and especially car ownership rates in the US mean this would be a permanently non-majoritarian project (though potentially potent within some cities).

An alternative, which I prefer on the merits as well as pragmatically, is too big to describe in detail here but the contours are by now well-established. It is, broadly, an urbanism of abundance. In high-demand cities,6 the playbook calls for land-use deregulation, building out viable transit networks, and making public space feel usable and safe for all. In suburbs and small towns, it includes allowing more multifamily housing, modular homes, and single-family rental homes. Obviously the details matter—and vary—place to place, but the goal is to make ownership of a home or a car less necessary to the enjoyment of first-class citizenship.

These goals, while seemingly uncontroversial, actually generate quite heated debate in practice and that debate splits existing political coalitions. The glass-half-full view is that this opens up an opportunity for across-the-aisle collaboration around abundance and YIMBYism, at least at some levels of government. I tend to agree that states are better positioned to take this sort of broad view than small cities or suburbs—but I think this is also sort of a cop out. Cities like New York and Chicago have the legal tools, intra-metro hegemony, and other ingredients they need to deliver on this and shouldn’t wait.

I’m using “liability” here in a colloquial sense of “obligations current and future,” which is a bit loose if we’re speaking in technical accounting language, where some of those might be better characterized as expenses. You can read a summary of these concepts in an accounting context here if you’re interested: https://www.investopedia.com/terms/l/liability.asp.

Houses generally depreciate in value. They are fighting a losing war of attrition with Mother Nature starting the day construction is completed. What more often appreciates is the land under the house, which is normally bundled with the house as part of the same transaction. This has been an obligatory Georgist footnote.

Obviously some people also rent by choice for a variety of reasons.

This is even before we get into non-financial barriers to car ownership and operation, like someone being too old to drive safely.

There’s probably not a huge amount of overlap between these groups because of the share of people who lack a license due to age reasons. Also, unlicensed ≠ non-car-owner, but presumably nearly every car owner has a license.

Land-use regulation does a lot more economic distortion in a place like Boston, which is in high demand, than in a place like Buffalo. By extension, Buffalo’s problems are less obviously amenable to remediation via law reform.

Thanks for your excellent analysis, Greg!

Affordability is an important but generally overlooked or undervalued planning goal.

One National Household Travel Survey asked respondents to prioritize transportation problems. The “Price of Travel” ranked the most important of six transport issues considered, indicating that affordability is an important concern to transport system users. Yet, transportation agencies and practitioners have no performance indicator for affordability. Instead, performance indicators (such as roadway level of service) and funding formula prioritize speed over other goals and therefore faster modes, such as automobiles and air travel, over slower but more affordable, inclusive and resource-efficient modes such as walking, bicycling and public transport.

Jeremy Mattson (2012), "Travel Behavior and Mobility of Transportation-Disadvantaged Populations: Evidence from the National Household Travel Survey," Upper Great Plains Transportation Institute (www.ugpti.org); at www.ugpti.org/pubs/pdf/DP258.pdf.

Related: this very good podcast from last week proposing a government program to provide lower cost mezzanine construction loans to jumpstart more affordable housing: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/odd-lots/id1056200096?i=1000662609844